Do you teach a language in addition to your translation work? Or do you have a pack of kids swarming your house this summer? “Alibi” is the game for you!

This works best for small groups (5-10 participants) and is fun for all ages. (Really. We tried it at an office party with the attorneys, and no one wanted to stop.) You might want to use this for intermediate language learners and above.

Set the scene: A crime or murder has been committed. Use some imagination to customize it for your group – for instance, someone stole all the cookies from the cookie jar. The police have narrowed it down to just two suspects, but unfortunately, the pair are providing an alibi for each other. Be a little specific here – such as, they say they were at the movies together at the time.

Choose the potential criminals: Now pick two people to be the suspects with the alibi, and ask them to leave the room for a minute before the interrogations. They should be corroborating their story now (for example, what movie did they see, where, and what time). In the meantime, explain to the rest of the group that they will be the interrogators. They should brainstorm a series of questions to try to catch the suspects in a lie.

Interrogate suspect one: Ask only one suspect back into the room. Sit the person in a chair facing the group, and let the questions begin. For writing practice, someone can be in charge of noting the answers. Go through about 3-5 minutes or 20 questions at this stage. The interrogators can improvise questions as they go. The suspect must answer (pretend to be their attorney if they try to use that defense to get out of playing).

Interrogate suspect two: You can ask the first suspect to leave, but it’s more fun if they stay – as long as they are quiet. Bring in the second suspect and go through questions agan. Ask the same or similar ones to see where their alibi is weak. Cap this stage, too, at 3-5 minutes or about 20 questions (unless you clearly catch the lie – then a questioner should holler “Aha!” and “the law” wins). You will likely catch the pair in a lie, but they might hold out – in which case, “the citizens” win.

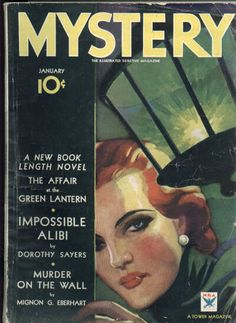

My favorite part of this game is that each round is equally fun. There aren’t many tricks you can learn that make it too easy for either side, and it doesn’t get vicious – people are too busy puzzling through the logic flow. Even your most reticent students will be itching to chime in. No one can resist a mystery…

What language games do you like, for fun or for class? How do you get shy people talking? Share in the comments below!